IT, Crowdsourcing and Crisis Mapping

4.3 Information Technology

Although still very common in the distribution of information to the general public, traditional printed communication forms offer no mechanism for two-way dialogue, nor do they enable people to share information in a manner that can be utilised, or retrieved by those who can respond, or do something with it.

Crisis mappers leverage mobile platforms, computational linguistics, geospatial technologies, and visual analytics to power rapid crisis response

The plethora of communications options available to connect the observations made during a crisis situation, and the centralised agencies responsible for addressing it

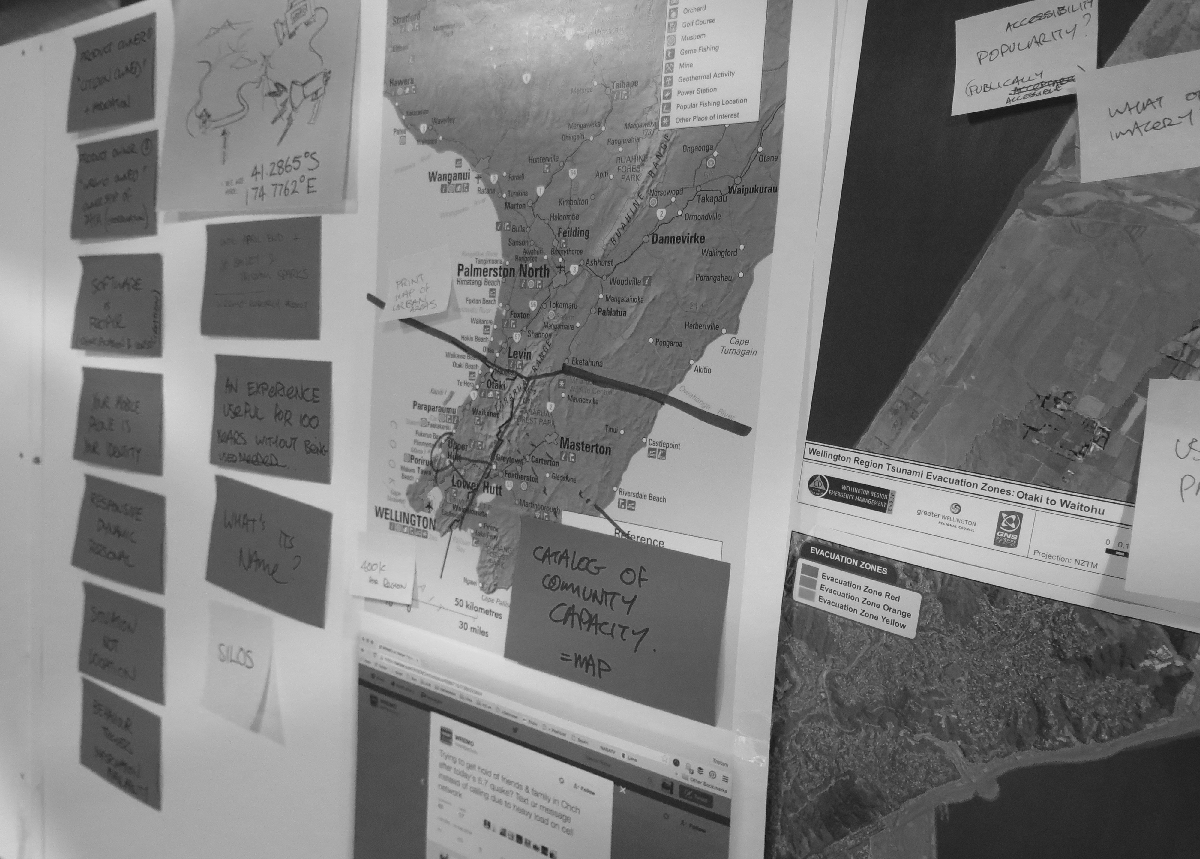

By using the available locational awareness, resilience and multimedia capabilities – tracking reports available in pre- and post-crisis situations – Prepare Wellington could become an invaluable resource for citizen and government alike.

While this research proposal recommends exploring and deploying new interaction opportunities on the smartphone in the first instance (partly due to their near ubiquity), eventually a responsive web experience can be provided on the same code base suitable for computers that rely on desktop and tablet displays, thus ensuring that the ability to contribute and confirm information is open to anyone outside of the crisis area.

4.4 Crowdsourcing

People want to do something to make the world a better place. They will help when they’re invited to. Access to cheap, flexible tools removes many of the barriers to trying new things. You don’t need fancy computers to harness cognitive surplus; simple phones are enough.

–(Shirky, 2010)

Crowdsourcing is a contemporary form of volunteering that takes advantage of the opportunity provided by online communications and programming. This is partly explained by Clay Shirky’s concept of “cognitive surplus”: communities who volunteer their time and labour, almost exclusively for an online output, in order that information based tasks are performed rapidly and at scale.

The aim of the first release of this product is to take advantage of a ‘mobile first’ strategy where the public can input and share geolocative data. In the Prepare Wellington region, this may take the form of logging potential resources or events.

Users outside of a crisis zone – perhaps following events via social media – should not be overlooked. These potential volunteers, with available ‘cognitive surplus’, ability and interest, may be invaluable in helping WREMO staff, volunteers and affected individuals in the crisis zone to contribute, police and qualify information input within Prepare Wellington.

In the words of Waikato Region Emergency Management Group, “Civil Defence is not one thing … We are all Civil Defence"

– (Waikato Civil Defence and Emergency Group, 2015)

4.5 Crisis Maps

The crowd has learned it can make its own map, they can jump on Twitter to learn breaking news before the news and can text and contribute to live, real-time and georeferenced maps during a crisis

Crisis maps are the real-time gathering, display and analysis of data in a crisis situation such as a natural disaster, period of political unrest or a conflict situation. These are usually short-term deployments active for the duration of weeks or months.

After the success of the defining crisis map platform Ushahidi in 2010, most iterations of crisis maps – especially those that have garnered publicity – have been ‘quick-up’ – ‘quick-down’ in nature (Hall, 2012).

These maps, generally undertaken by Volunteer & Technical Communities (V&TCs) such as the Standby Task Force (www.standbytaskforce.org) react quickly to an unfolding crisis. The Haiti Earthquake (Meier, 2012), the Japanese Tsunami (Seki, 2011), and the Christchurch Crisis Map (Beatson, Buettner, & Schirato, 2014) were all in this mode.

There are few examples of crisis maps established for long-term deployment. Bushfire Connect was a crowdsourcing and alerting system that was continually active throughout the fire season in Australia. It existed for about two years (up to the end of 2012) but did not continue as it was unsuccessful in securing funding and it was not feasible to sustain it on a volunteer basis (Hall, 2012). Prepare Wellington will a be a pioneer in the space of ‘permanent’ crisis maps that serve their immediate populations.

Powered by the web, V&TCs are by nature decentralised and non-hierarchical. They are also unencumbered by bureaucracy, do not need to adhere to system or protocol, and can deploy software quickly.

In a crisis situation, other maps will, undoubtedly, appear. In Christchurch (2011) three crisis maps were initially deployed (Beatson, Buettner, & Schirato, 2014, p41). It has been observed that “the crowd has learned to first ask: Who is [setting] up the Crisis Map?… it is better to converge and swarm around a single crisis map … to help the system find that equilibrium” (Ziemke, 2012, p106). Becoming ‘the map’ will require due consideration and inclusion of the V&TCs and local volunteers.

4.6 Crisis phase model

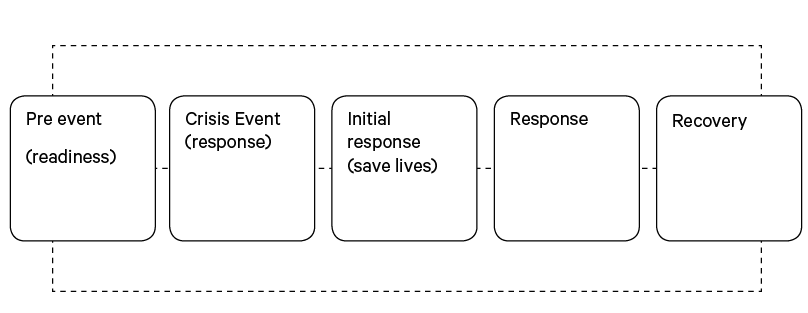

WREMO operates on the basis of a series of status levels or crisis phases that have been used as a model for the Prepare Wellington design research project.

Unlike the standard crisis maps model where deployments are “ramped up and continue for a limited period, based on volunteer effort only” (Hall, 2012), Prepare Wellington needs to remain active at all times, and offer engagement opportunities and information relevant to the user’s situation.

Interrogation of this model allowed for the inclusion of functions within the design of the experience that, beyond the mitigation and preparedness phases, might address predictable changes in psychological health (such as post traumatic stress), following extended time in a crisis area.

Crisis phases used to define status in Prepare Wellington.

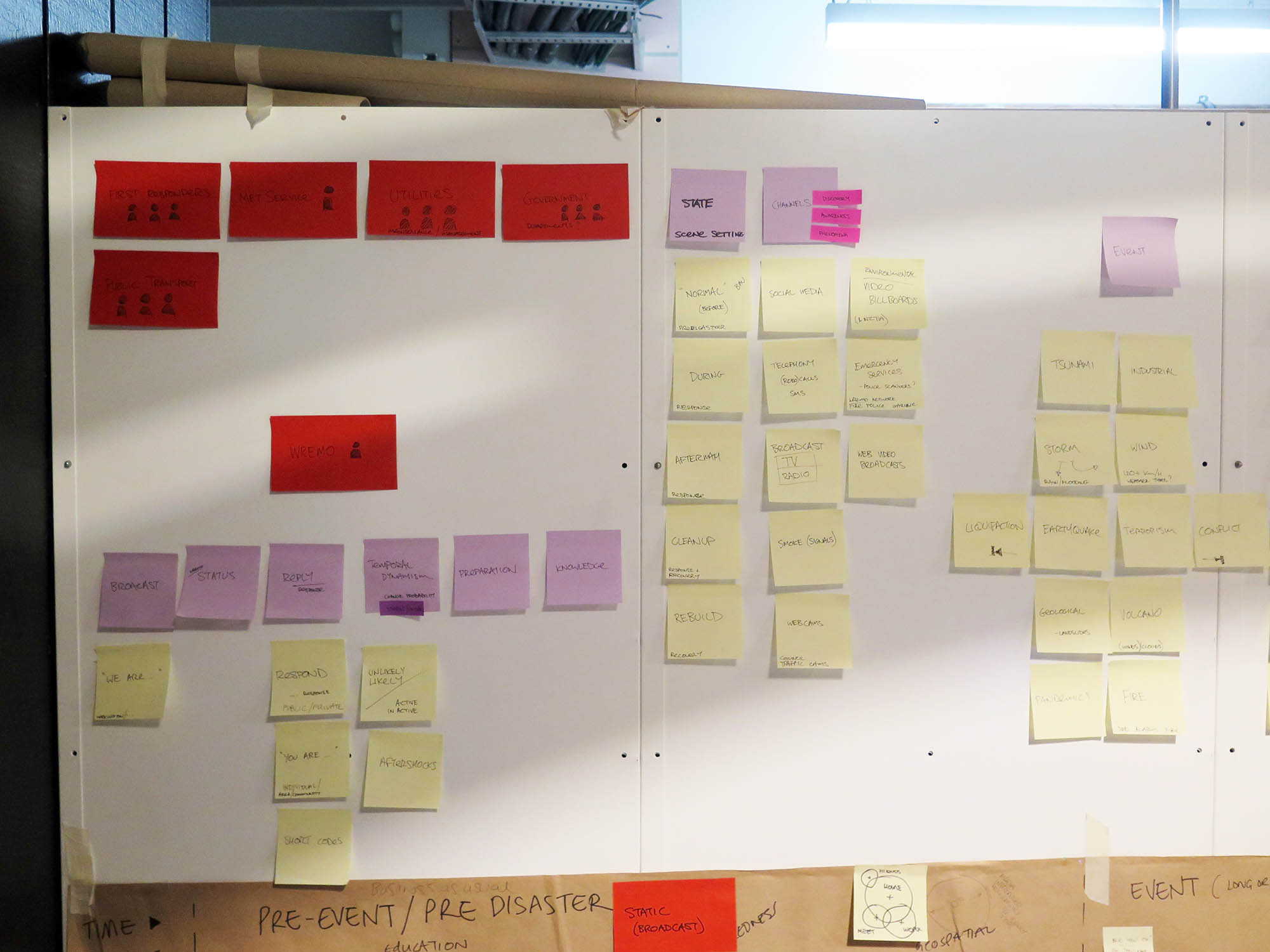

Project workspace May 2016